#it’s on every app it’s on Twitter every meme has a stake ad it’s on every sport channel in every stadium

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

does anyone else feel really fuckin weird about the sheer amount of gambling being pushed from literally everywhere

or is that just me

#it’s on every app it’s on Twitter every meme has a stake ad it’s on every sport channel in every stadium#everyone wants your money as much as possible and will gladly exploit addictions to fleece your pockets

89 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Since my last news update in March, today I’m dissecting everything that has come out of the woodwork in April and May regarding Dragon Age 4. So, get some tea and let’s get this show on the road, because we’ve got over 4,000 words of news to delve into!

Reveal? (game shows/new hire/remaster):

Following the cancellation of E3, EA Play 2020 Live has been officially confirmed as a digital show, taking place on June 11th, at 4:00 pm PST / 7:00 pm EST.

Before the outbreak cancelled E3 2020, we knew Mike Gamble, the Project Lead on the next Mass Effect game had plans to make a physical appearance at E3/EA Play. So, the question remains, will BioWare still have a presence at EA Play this year?

Mike Gamble is one of the key members of the Mass Effect team, I highly doubt he’s talking about revealing the next Mass Effect game which is currently in very early stages of development, and won’t release until after Dragon Age 4. Perhaps, Mike back in 2019 was hinting at revealing the heavily rumoured Mass Effect Remaster this EA Play?

Earlier in May, EA had a quarterly conference call and it revealed some fascinating information regarding future unannounced titles. Currently, EA have “one more EA HD title, Four EA Partner titles and two mobiles games still unannounced”. Also, EA said "multiple titles" are set to launch on Nintendo Switch this year.

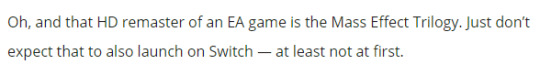

The EA HD title refers to a remaster of an EA game, hence why most people are speculating at the Mass Effect Trilogy. Venturebeat went on to officially state that this title was indeed the Mass Effect Trilogy.

So, there’s one rumoured possibility for the Mass Effect Trilogy Remaster to be revealed this EA Play, which is cool! BioWare may have a presence this year after all! But I know you all didn’t come for Mass Effect; you came for Dragon Age. So, what do we know about that franchise and a potential reveal?

Jo Berry, a Writer at EA retweeted EA Play Live’s announcement with a party emoji! 👀

This could be absolutely nothing, but at a whim, perhaps a reference to a Dragon Age 4 teaser, or EA Motive’s new I.P since she has worked within both teams....

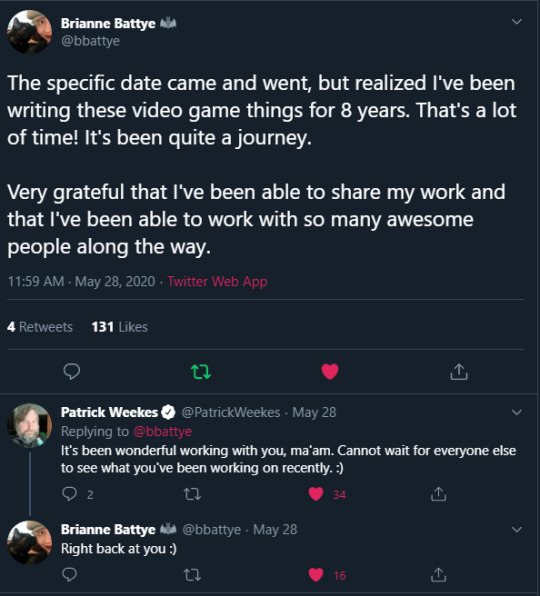

On top of that, Brianne Battye, Writer at BioWare tweeted about her 8-year journey at BioWare. She’s very grateful for sharing her work, and the awesome people she’s worked with along the way.

Patrick Weekes replied saying they: “Cannot wait for everyone else to see what you've been working on recently. :)”

Then, Brianne said: “Right back at you :)”

Two HUGE witters on the Dragon Age team are excited for everyone else to see what they’ve all been working on recently! 👀 When I saw this tweet, I was trying to stay calm and keep my expectations low, but come on when you see a tweet like this, you just get so excited! The question is, when will we see what they’ve been working on, and is it anytime soon? Please?

Well, there is something else we need to talk about that may relate to a potential tease.

Hilary Heskett, who used to be EA’s Global Product Manager has returned to work at EA and BioWare. Put simply, she’s a Digital Marketer for BioWare.

Hilary; particularly, was heavily involved in Dragon Age: Inquisition’s marketing! In fact, the majority of her work at EA involved representing BioWare as a brand online creating trailers, key art, screenshots, packaging, and advertisements. So, it’s a fair assumption that she’ll be fulfilling the exact same role for future BioWare titles like Dragon Age 4.

With Hilary joining the team at this point in development, could the marketing stages of Dragon Age 4 soon begin, perhaps at EA Play? Or later on in 2020? Or is she going to be marketing the Mass Effect Remaster?

I sound impatient, but, in the past BioWare have a habit of starting the marketing stages of their products at least two years before an initial release.

With that, we’ve got to ask ourselves, is hiring a marketer at this point in time a mere coincidence? or is it preparation for when marketing does start? Are we on the verge of seeing Dragon Age 4 official content soon?

Not to waffle on, because we’ve got a lot to talk about in this video, but I was hired as a Digital Marketer for an app company in the UK. As I understand it, you normally enter projects, mid-to-end of production, because what would a marketer do in the early stages logically? Your role is to be there for the advertising of the product.

So, in BioWare’s case, it's my understanding that Hilary has joined the team with one year full-swing production, is she about to begin the marketing stages of the next Dragon Age game? Is the game ready for that stage? If anything, I think with Hilary’s background, she’s the perfect person to market Dragon Age 4.

On top of EA Play, Geoff Keighley announced Summer Game Fest, a new industry-wide celebration of video games. Showcasing digital news, In-game events, & playable content. EA are headlining the event with EA Play, but there are many other world premieres spread throughout the summer. So, there’s a potential for other trailer reveals later on in the year, not to mention The Game Awards.

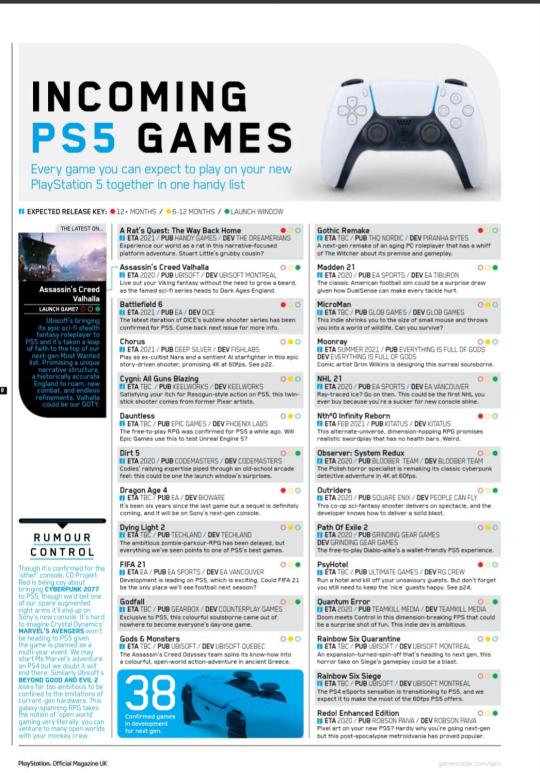

And, there’s also this leak that shows Dragon Age 4 on a list of PS5 games from the newest issue of PlayStation magazine UK. PlayStation are having an event on June 4th, so we’ll find out if this leak is true soon enough.

If we’re going to see anything Dragon Age 4 related this year, EA Play is the biggest contender for a reveal. I know the whole world could do with that right now! At this current moment, there is no schedule for the show. However, Saria, myself, Fusselkorn and maybe other content creators will be streaming EA Play, no matter what, so turn those reminders on and come join us in our clown suits.

Development (teases/production):

Moving on to teases and development updates. Currently, BioWare are hiring a ‘Senior Outsource Producer.’

This is a pretty big deal, to those who don’t know what a ‘Senior Outsource Producer’ would do...

“Outsourcing development means to hire out any process of a business to third party. The process helps your company or organization to grow.”

To grant more perspective, during Mass Effect: Andromeda’s development, major aspects of the game's animations were outsourced to other EA studios.

However, this isn’t going to be the same for Dragon Age 4, this role is for one Producer to help the outsourcing team into a robust and comprehensive department that supports BioWare projects in all aspects of development.

I have friend in triple AAA games, and they had something to say about outsourcing regarding Dragon Age 4: “To be honest, I'd say (outsourcing is) different per studio due to scope. But with something big like Dragon Age I'd probably say outsourcing would start early to mid-production as they have a hell of a lot to do. Some studios outsource from the get go though so that's also possible. And It's rare that outsourcing starts in the final leg of development.”

What I understand from the job posting is that BioWare are looking to hire a producer who will be dedicated to outsourcing so they can establish a pipeline and maintain proper standards for outsourcing. This hiring was posted in May, so the studio might be a few months early from when they actually have to outsource. However, this process will be coming up soon in major development.

Moving on. In early April, Mark Darrah went on a twitter rampage sharing many tweets relating to Dragon Age 4. One tweet stated: “Is tweeting more going to make you all speculate more or less?”. Followed by a poll with the answers “more”, “less” & “Dragon Age 4!?”

The following week, Mark Darrah teased his three Wolf-Rook books he has placed on a shelf at home.

Later on, in the month, he decided to stack each of them, prompted with the caption: “Spoiler: these are a terrible building material…”

Just last week, Mark tweeted the Wolf-Rook book once more, with the following meme: “Dear men, what is preventing you from looking like this?”

This cheeky tease encouraged Melissa Janowicz (Gameplay Designer) to join the fun and share her own Wolf-Rook book! She said: “It's an absolutely gorgeous book. I'll treasure it for life.”

Ahhh. The secrets these books could hold about Dragon Age 4’s core concepts.... And Mark Darrah is just staking them together, making book forts out of them, as you do! 😂 Maybe one day, we’ll uncover the secrets held within every page, but that day is not yet upon on.

On the same memey day, Chris Anderson, (Application Development/Publishing Support at BioWare) tweeted: “Other people are teasing things, so what the hell, here's an image that I used in something I was working on today.” With a pink image shown.

Chris and Melissa followed a Twitter conversation about pink being the “perfect colour for when you need something that screams temp.”

Basically, this pink actually has some context for the development of Dragon Age 4. ‘Temp’ means temporary textures, the first blocked out layer of a texture before actual detailed textures are added.

This can refer to many scenes or models in the early texturing phases, as art assets are still in the approval stages. On a wild, out-there whim, perhaps the team are wrapping up a trailer for a reveal? Maybe?... please?

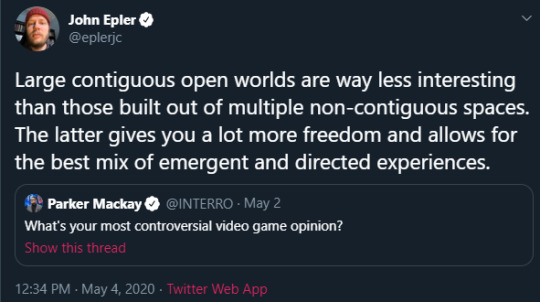

John Epler (Narrative Director) shared his most controversial opinion of all time:

I loved the Hinterlands, but as a fan of the previous Dragon Age game’s ‘linear with freedom' approach, I appreciate John’s take on open world’s since Dragon Age: Inquisition, perhaps this will shape the way forward for future BioWare titles?

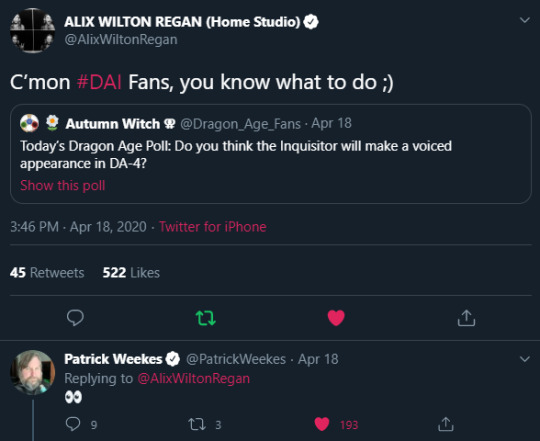

Alix Wilton Regan, voice actress of the Female British Inquisitor retweeted Autumn Witch’s poll asking if people believe the Inquisitor will return as a voiced appearance in Dragon Age 4. Alix tweeted: “C’mon #DAI Fans, you know what to do ;)”

Patrick Weekes replied to Alix’s post with an eye's emoji 👀.... I think I speak for everyone when I say, in some capacity, the Inquisitor has got to return in the next game!

In another tweet, Patrick Weekes teased potential new companions when a Twitter trend placed 5 Dragon Age characters in 6 different camps went around the platform.

When choosing their preferred camp, Patrick Weekes tweeted: “Finally, in Camp 7, it's turned into a bit of a mess, with coffee grounds spilled everywhere and the couch inexplicably on fire after a drinking game gone wrong. But that's another story.”

Of course, there’s not much to tear apart here, but we have acknowledgement of the next party members! It sounds like they’re a wild bunch already!

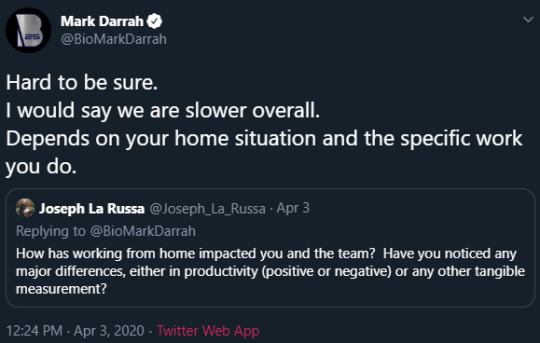

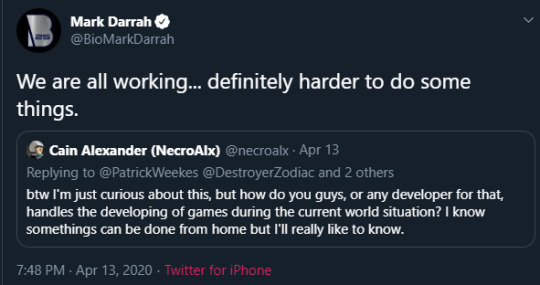

In early April, Mark Darrah answered a few current development tweets:

So, that’s...Splendid.

Karin Weekes (Editor) tweeted that they “got to sort/catalog/document updates to made-up languages at work today.”

Following that tweet, @ladyiolanthe asked Karin: “Do you think BioWare might ever be able to release Qunari, Dwarvish, and Elvhen lexicons in a World of Thedas Volume 3 sort of book? Or is that unlikely since they're ciphers and maybe there isn't a standardized grammatical structure, etc?”

Karin replied with: “That’s an interesting idea - I, for one, would find it a hoot! I might send out some feelers…” Any books of made-up languages I can get my hands on would be greatly appreciated!

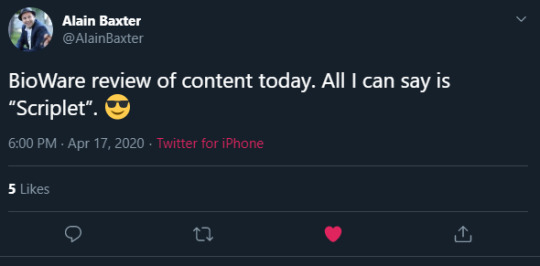

Alain Baxter, (‘Production guy’) tweeted: “BioWare review of content today. All I can say is “Scriplet”. 😎

Apparently a ‘Scriptlet’ is an action verb. Alain is teasing premature scripts as they ‘perform their function’ So, something exciting is going down in the scripts, to be worked on in-engine. Or maybe it’s just an inside joke?

John Epler tweeted a great design message about “how 90% of ‘bad’ decisions are, in fact, the best decision at the time. For John, that will always be the camera zoomed conversations in DA: I. People didn’t like it, and asked why not just make them full scenes. But that’s not the decision they make in-house. It was 'make them simple conversations or else cut them'. Game dev is all about making the best decision you can at the time, with the resources you have .A lot of stuff you thought was weird or awkward came down to a gut call of 'this is the best I can make this and I trust it's good enough'. Sometimes we're right, sometimes not.”

Awesome words to think on, Dragon Age 4 will be amazing, I’m sure, but just remember to set your expectations right and realise everything design-wise, happens for a reason.

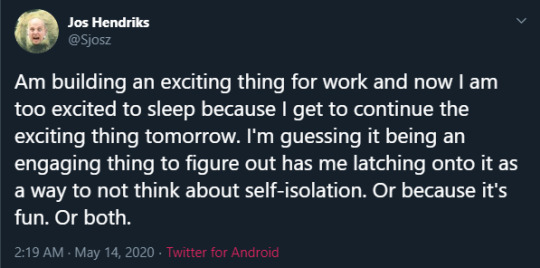

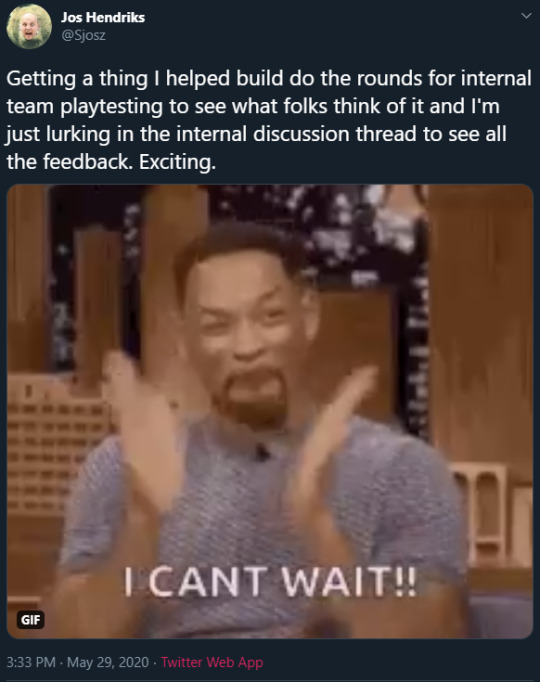

Shifting to other design aspects. Jos Hendricks (Senior Level Designer) tweeted:

Mike Jungbluth (Animation Director) tweeted: “Just reviewed something in game that hit THIS LEVEL! Hot damn, moments like this are what I live for.”

Both tweets are incredibly excited and telling of development for Dragon Age 4, it sounds like they’re building and prototyping an epic scene equivalent in scale to the attack at Haven scene? Perhaps, Solas destroying the Veil? Who knows, but it sounds epic, and I’m living for both dev.'s enthusiasm!

For the final tweet regarding the development side is from Åsa Roos (Principle UX Designer)

A UX designer writing about Solas? That must be for codex entries? Right? More lore on our Rebel God!

Unannounced Dragon Age Game:

In my previous March news update, I discussed brashly about the developers on Dragon Age 4 still claiming that this project has not officially been announced yet, however, The Dread Wolf Rises teaser in 2018 certainly alluded to an announcement regarding the next Dragon Age title. Following this story, we have many sources providing clarity on Dragon Age 4’s current ‘unannounced’ situation.

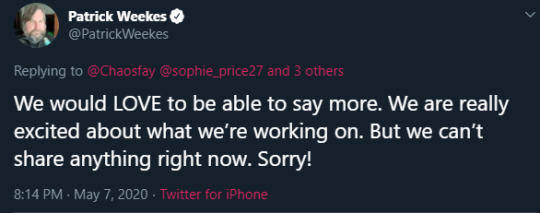

Patrick Weekes confirmed that they are “working on an unannounced game in the Dragon Age universe.”

Patrick said: “We would LOVE to be able to say more. We are really excited about what we’re working on. But we can’t share anything right now. Sorry!”

In April 2019, I painted this unannounced situation rather conspiratorial, I said that perhaps the Dragon Age dev’s can’t share anymore on the next game because Anthem was the next project, and EA are forcing them to not speak on Dragon Age. In an attempt to maintain the crowd by not letting BioWare developers regard Dragon Age 4 as the next working project in the works.

However, I don’t think it’s that deep. I think the developers are just under an NDA, and literally can’t speak about the game.

In Episode 121 of the Anthem-based ‘Freelancer Codex’ Podcast - as a guest, Melissa Janowicz shared that the developers on the secret Dragon Age team cannot talk about the next game, in fact, they can barely talk about the contents of The Dread Wolf Rises teaser trailer.

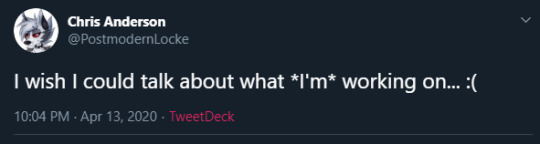

Chris Anderson also emphasised this same point in a tweet:

As a side not, someone asked Chris why not lie and come up with fake answers to fool the fans, and Chris said: “That can, unfortunately, get me in nearly as much trouble!”

Which shows the validity and value in BioWare developer tweets. The developers can’t just lie about the project either. Which honestly helps someone like me out.

As we know, a game is coming, yet it’s still is very much unannounced, probably because as Jason Schreier reported in 2018, Dragon Age 4 is going to change at least 5 times in the next two years, perhaps BioWare don’t want to show us anything because they don’t want to set anything in stone, or show gameplay that is not representative of the final game.

But that doesn’t extend to a CGI trailer, or a full title drop, Maker knows that would be amazing, and is within the realm of possibility.

New Lore/Fun:

We have some new lore, and other fun things I wanted to share.

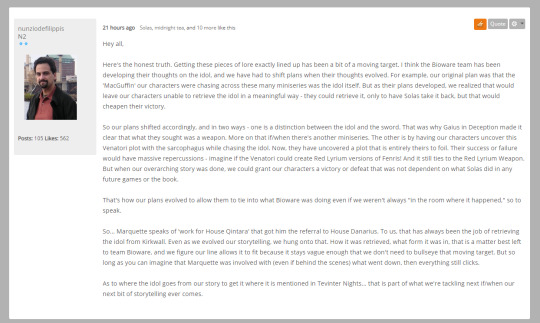

Dragon Age Comic Writer, Nunzio DeFillipis talked HUGELY about the red lyrium idol and what was originally planned for their comics.

Nunzio recently mentioned in the Unofficial Bioware Forums that the comic characters from Deception were originally chasing the red lyrium idol.

Nunzio stated that the original plan for the comics would've had the characters retrieve the red lyrium idol. Only to have Solas take it back. Eluding to the idol's planned whereabouts before the plot changed since Joplin's cancellation and BioWare's shift regarding this idol in the comics.

Does this still mean that the location of the red lyrium idol is most likely in the hands of Solas and might only be discovered in Dragon Age 4? Or does the next protagonist have a shot at retrieving the idol before Solas finds it?

It seems like a bummer that the original comic idea was scrapped and the writers were forced to change narrative direction regarding this particular idol.

As a funny tweet I saw. Emily (Domino) Talyor tweeted using her overheard in the office hashtag:

BioWare dev’s can’t even tell their kids, folks.

And, regarding the Fuzzy Freaks livestream. Patrick Weekes’s response to my question, asking how does Solas kill dwarves in their sleep if they have no connection to the Fade, was “very effectively.” This will be a mystery I will personally be investigating when we have our hands on the game.

Considering it was really fun for those who watched the Fuzzy Freaks livestream, I’m going to share other silly takeaways:

Patrick Weekes doing a New York accent for the Carta Dwarf is amazing!

“DREAD DUMBASS” - is a jokey dialogue option that Karen Weekes scribbled notes for future reference.

Patrick likes soft romances and happy endings! IRONICALLY.

Patrick’s style of writing is less high fantasy and more modern.

@DrunkDalish, Co-founder of Dragon Age Day interviewed both Karen and Patrick Weekes. As a lover of Dragon Age lore, these interviews reveal so many loving tidbits that you should read for yourself. However, something I noted that was very significant regarding the future is based on Masked Empire’s ending. So, spoilers for that, but Felassan’s fate isn’t what it seems. Perhaps this elf could come back in the future if needed.

Wellbeing:

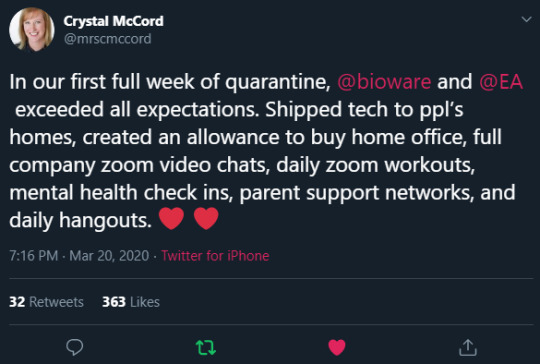

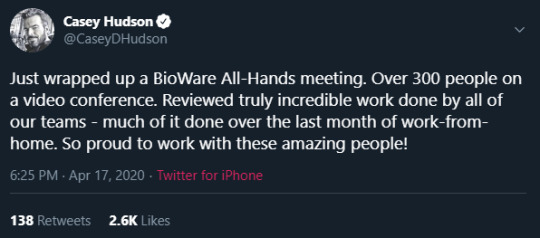

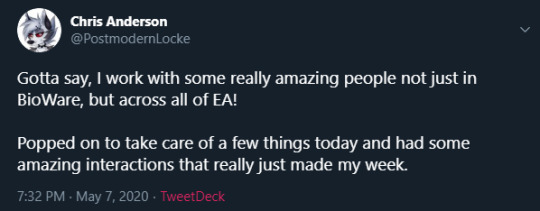

And, we come to the last topic, this one is centred on the BioWare staff’s wellbeing. Last year, there was a Kotaku article revealing the crunch and working conditions at BW, there was a lot of worry and confusion in the air that the people working on these games were struggling mentally because of senior management and many other reasons. With that in mind, I’m dedicating a section in these news updates to the wellbeing of the developers, any signs/tweets of positivity and hope will be shared in an effort to see if there has been any change in the BioWare offices since Anthem’s release.

It seems like things are going pretty well and people seem happy and optimistic about the next Dragon Age.

If there are any major updates to a Dragon Age 4 tease at EA Play, I'll be sure to make an update video, but otherwise, be sure to join our livestream as see for ourselves what waits us this EA Play.

Let me know your thoughts down below, what do you think about a potential EA Play teaser, where are your expectations at?

#dragon age 4#dragon age 4 news#dragon age 4 news update#solas#clown solas#dragon age 4 trailer#the dread wolf rises#solas the dread wolf#thedas#tevinter#solas dread wolf#dragon age news#the next dragon age#mass effect trilogy#ea play 2020#dragon age ea play#da4#dragon age imperium#dragon age developers#dragon age development#EA#BioWare#the dread wolf#tevinter nights#major development#dragon age 2022#next dragon age#next mass effect#BioWare Edmonton#dragon age 4 update

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

OTT in the time of COVID-19: Using social to drive adoption

30-second summary:

Historically, OTT brands excel in social media marketing by using their original content as the centerpiece of their ads. While many are consuming content on social channels, OTT brands can utilize this unique content to persuade users to tune into their offering.

In addition to the number of eyeballs available via social media at this time, another opportunity for OTT brands is presented in the fact that the space is less crowded with many pausing media efforts due to affected business operations, sensitives and more.

As OTT platforms and studios are promoting their new movies, they must take well thought out steps. First, they must figure out what their objective is. Next, identify the target audience for the movie itself and align it to which social platform makes the most sense.

Video is always the best option for OTT platforms since that is their primary output. For shows and films alike, trailer-specific content is readily available and can be adjusted into six second or 30 second cuts to post across various social media outlets.

For OTT brands, direct to home releases could be a norm for them going forward. As such, during this time they should build good partnerships with movie studios while they have the upper hand.

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, OTT platforms are experiencing a unique moment. With millions at home, people are craving new content.

According to PMG partner insights, Pinterest has seen incredible YOY spikes in engagement, including a 60% jump in searches, a 30% boost in sign-ups and a 43% increase in board creation. Meanwhile, YouTube captures 10M search queries and billions of views worldwide related to COVID-19 authoritative news coverage every day and Reddit is experiencing double-digit growth in site visits.

Considering how much you’ve likely seen about ‘Tiger King’ on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, it’s no surprise that many are turning to the likes of Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hulu to bide their time.

Because of the major disruptions caused by COVID-19, these OTT platforms have even become landing pads for feature films and studios as they respond to movie theater closures.

As such, we’ve seen rapid home releases of Invisible Man, The Hunt and Emma, and SXSW will premiere its film lineup on Amazon Prime Video.

Additionally, with fans yearning for sports content, ESPN has announced that the release of its anticipated 10-part series about Michael Jordan, The Last Dance, has been pushed from June to April.

As OTT offerings continue to grow and change, social media platforms are an effective channel to drive OTT adoption rates while offering much-needed escapist content.

The social media landscape during COVID-19

With events and entertainment in the outside world put on hold, people are turning to social media for escape and distraction, whether it be watching celebrities and musicians on Instagram Stories or tagging each other in memes across a variety of platforms.

Content creation is on the rise – TikTok and Twitch, two of the main creator channels, are experiencing a significant jump in videos and streams as creators and consumers alike seek an outlet.

This increased consumption creates a massive opportunity for OTT brands to get in front of a large and engaged audience.

Historically, OTT brands excel in social media marketing by using their original content as the centerpiece of their ads. While many are consuming content on social channels, OTT brands can utilize this unique content to persuade users to tune into their offering.

This is all part of the continued trend of growing OTT promotion via social media. Being a competitive landscape, OTT brands are fighting hard for people’s subscriptions.

Quibi, a mobile short-form video platform, spent millions on social media advertising, even before its April 6th launch. They clearly understood the stakes and wanted to take advantage of a wide audience at home.

Cautious opportunities for OTT brands

In addition to the number of eyeballs available via social media at this time, another opportunity for OTT brands is presented in the fact that the space is less crowded with many pausing media efforts due to affected business operations, sensitives and more.

However, advertising during this crisis, of course, requires a hypersensitive evaluation of tone. Internal teams must adopt a heightened scrutiny of their messaging and approach to ensure that content strategy is relevant, effective, and sensitive to the situation at hand.

Navigating OTT promotion via social media

For movie studios, an OTT platform release is very different from a typical theater release. Historically, studios would get the word out that a movie was available through a spray and pray approach with high impact media placements.

With OTT listings, they also need to educate the audience on which platform it’s available through. This adds another element to get across in promotions and requires studios to analyze if they’re actually convincing people to adopt streaming services.

As OTT platforms and studios are promoting their new movies, they must take well thought out steps.

First, they must figure out what their objective is. Is it awareness of the movie or movie streams? Ideally, it’ll be a solid mixture of both. It’s important that people know the movie exists but also to know exactly where it’s available so they can act on it.

Next, identify the target audience for the movie itself and align it to which social platform makes the most sense.

YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram are already major players and should be part of every social media plan due to these platforms’ expansive reach and targeting capabilities — but there are other options to explore.

For example, younger audiences can be reached through TikTok and Snapchat. Pinterest is traditionally a great avenue for mothers who are looking for ideas of what to do with kids at home, making it great for promoting family-focused content.

Meanwhile, Twitch and Reddit can reach tech-driven and male-skewed audiences. It’s important that teams think carefully to ensure they’re reaching the right people, in the right way, during this sensitive time.

Video is always the best option for OTT platforms since that is their primary output. For shows and films alike, trailer-specific content is readily available and can be adjusted into six second or 30 second cuts to post across various social media outlets.

Another way to be creative includes slide shows with three to five static images to flip through on Facebook and Instagram.

The increase in livestreaming during this time provides an opportunity for marketers to leverage their content, as well as actors and directors. Doing so on Facebook and Instagram and other daily apps offers a more personal connection than clean, edited videos.

The new normal – OTT brands beyond COVID-19

My husband and I have a movie night every other week where we are loyal to one dine-in theater. We decided to replicate this during our quarantine as we heard The Hunt was available on Amazon Cinema.

We saw that it was $20 to stream which is similar to how much we would spend for two theater tickets. We had dinner delivered through UberEats, sat down on our couch, and watched the movie. This was a definite change, but one we might do in the future if we can watch new movies right at home.

For OTT brands, direct to home releases could be a norm for them going forward. As such, during this time they should build good partnerships with movie studios while they have the upper hand.

With the world rapidly changing, the world post COVID-19 will be a different one. However, we can be certain that OTT platforms will continue to bring people together with content that everyone can share. And while the Tiger King memes will fall off eventually, there will be plenty of OTT promotion and chatter on social media right around the corner.

Ting Zheng is a social account lead at PMG where she leads channel strategy and execution for some of the world’s biggest B2B, travel, technology and retail brands.

The post OTT in the time of COVID-19: Using social to drive adoption appeared first on ClickZ.

source http://wikimakemoney.com/2020/05/14/ott-in-the-time-of-covid-19-using-social-to-drive-adoption/

0 notes

Text

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider http://www.nature-business.com/nature-saudis-image-makers-a-troll-army-and-a-twitter-insider/

Nature

Image

Online attackers who targeted Jamal Khashoggi were part of a broad effort ordered by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his close advisers to silence Saudi critics.CreditCreditChris J. Ratcliffe/Getty Images

Each morning, Jamal Khashoggi would check his phone to discover what fresh hell had been unleashed while he was sleeping.

He would see the work of an army of Twitter trolls, ordered to attack him and other influential Saudis who had criticized the kingdom’s leaders. He sometimes took the attacks personally, so friends made a point of calling frequently to check on his mental state.

“The mornings were the worst for him because he would wake up to the equivalent of sustained gunfire online,” said Maggie Mitchell Salem, a friend of Mr. Khashoggi’s for more than 15 years.

Mr. Khashoggi’s online attackers were part of a broad effort dictated by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his close advisers to silence critics both inside Saudi Arabia and abroad. Hundreds of people work at a so-called troll farm in Riyadh to smother the voices of dissidents like Mr. Khashoggi. The vigorous push also appears to include the grooming — not previously reported — of a Saudi employee at Twitter whom Western intelligence officials suspected of spying on user accounts to help the Saudi leadership.

The killing by Saudi agents of Mr. Khashoggi, a columnist for The Washington Post, has focused the world’s attention on the kingdom’s intimidation campaign against influential voices raising questions about the darker side of the crown prince. The young royal has tightened his grip on the kingdom while presenting himself in Western capitals as the man to reform the hidebound Saudi state.

This portrait of the kingdom’s image management crusade is based on interviews with seven people involved in those efforts or briefed on them; activists and experts who have studied them; and American and Saudi officials, along with messages seen by The New York Times that described the inner workings of the troll farm.

Saudi operatives have mobilized to harass critics on Twitter, a wildly popular platform for news in the kingdom since the Arab Spring uprisings began in 2010. Saud al-Qahtani, a top adviser to Crown Prince Mohammed who was fired on Saturday in the fallout from Mr. Khashoggi’s killing, was the strategist behind the operation, according to United States and Saudi officials, as well as activist organizations.

Many Saudis had hoped that Twitter would democratize discourse by giving everyday citizens a voice, but Saudi Arabia has instead become an illustration of how authoritarian governments can manipulate social media to silence or drown out critical voices while spreading its own version of reality.

“In the Gulf, the stakes are so high for those who engage in dissent that the benefits of using social media are outweighed by the negatives, and in Saudi Arabia in particular,” said Marc Owen Jones, a lecturer in the history of the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula at Exeter University in Britain.

Neither Saudi officials nor Mr. Qahtani responded to requests for comment about the kingdom’s efforts to control online conversations.

Before his death, Mr. Khashoggi was launching projects to combat online abuse and to try to reveal that Crown Prince Mohammed was mismanaging the country. In September, Mr. Khashoggi wired $5,000 to Omar Abdulaziz, a Saudi dissident living in Canada, who was creating a volunteer army to combat the government trolls on Twitter. The volunteers called themselves the “Electronic Bees.”

Eleven days before Mr. Khashoggi died in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, he wrote on Twitter that the Bees were coming.

Swarming and Stifling Critics on Twitter

One arm of the crackdown on dissidents originates from offices and homes in and around Riyadh, where hundreds of young men hunt on Twitter for voices and conversations to silence. This is the troll farm, described by three people briefed on the project and the messages among group members.

Image

The Saudi government has hired hundreds of men to harass detractors on Twitter, which has had trouble combating their attacks.CreditDavid Paul Morris/Bloomberg

Its directors routinely discuss ways to combat dissent, settling on sensitive themes like the war in Yemen or women’s rights. They then turn to their well-organized army of “social media specialists” via group chats in apps like WhatsApp and Telegram, sending them lists of people to threaten, insult and intimidate; daily tweet quotas to fill; and pro-government messages to augment.

The bosses also send memes that their employees can use to mock dissenters, like an image of Crown Prince Mohammed dancing with a sword, akin to the cartoons of Pepe the Frog that supporters of President Trump used to undermine opponents.

The specialists scour Twitter for conversations on the assigned topics and post messages from the several accounts they each run. Sometimes, when contentious discussions take off, they publish pornographic images to goose engagement with their own posts and distract users from more relevant conversations.

Other times, if one account is blocked by too many other users, they simply close it and open a new one.

In one conversation viewed by The Times, dozens of leaders decided to mute critics of Saudi Arabia’s military attacks on Yemen by reporting the messages to Twitter as “sensitive.” Twitter automatically hides such reported posts from other users, blunting their impact.

Twitter has had difficulty combating the trolls. The company can detect and disable the machine-like behaviors of bot accounts, but it has a harder time picking up on the humans tweeting on behalf of the Saudi government.

The specialists found the jobs through Twitter itself, responding to ads that said only that an employer sought young men willing to tweet for about 10,000 Saudi riyals a month, equivalent to about $3,000.

The political nature of the work was revealed only after they were interviewed and expressed interest in the job. According to the people The Times interviewed, some of the specialists felt they would have been targeted as possible dissenters themselves if they had turned down the job.

The specialists heard directors speak often of Mr. Qahtani. Labeled by activists and writers as the “troll master,” “Saudi Arabia’s Steve Bannon” and “lord of the flies” — for the bots and online attackers sometimes called “flies” by their victims — Mr. Qahtani had gained influence since the young crown prince consolidated power.

He ran media operations inside the royal court, which involved directing the country’s local media, arranging interviews for foreign journalists with the crown prince, and using his Twitter following of 1.35 million to marshal the kingdom’s online defenders against enemies including Qatar, Iran and Canada, as well as dissident Saudi voices like Mr. Khashoggi’s.

For a while, he tweeted using the hashtag #The_Black_List, calling on his followers to suggest perceived enemies of the kingdom.

“Saudi Arabia and its brothers do what they say. That’s a promise,” he tweeted last year. “Add every name you think should be added to #The_Black_List using the hashtag. We will filter them and track them starting now.”

A Suspected Mole Inside Twitter

Twitter executives first became aware of a possible plot to infiltrate user accounts at the end of 2015, when Western intelligence officials told them that the Saudis were grooming an employee, Ali Alzabarah, to spy on the accounts of dissidents and others, according to five people briefed on the matter. They requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

Mr. Alzabarah had joined Twitter in 2013 and had risen through the ranks to an engineering position that gave him access to the personal information and account activity of Twitter’s users, including phone numbers and I.P. addresses, unique identifiers for devices connected to the internet.

The intelligence officials told the Twitter executives that Mr. Alzabarah had grown closer to Saudi intelligence operatives, who eventually persuaded him to peer into several user accounts, according to three of the people briefed on the matter.

Image

Before his killing, Mr. Khashoggi was starting projects to combat online abuse.CreditShannon Stapleton/Reuters

Caught off guard by the government outreach, the Twitter executives placed Mr. Alzabarah on administrative leave, questioned him and conducted a forensic analysis to determine what information he may have accessed. They could not find evidence that he had handed over Twitter data to the Saudi government, but they nonetheless fired him in December 2015.

Mr. Alzabarah returned to Saudi Arabia shortly after, taking few possessions with him. He now works with the Saudi government, a person briefed on the matter said.

A spokesman for Twitter declined to comment. Mr. Alzabarah did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Saudi officials.

On Dec. 11, 2015, Twitter sent out safety notices to the owners of a few dozen accounts Mr. Alzabarah had accessed. Among them were security and privacy researchers, surveillance specialists, policy academics and journalists. A number of them worked for the Tor project, an organization that trains activists and reporters on how to protect their privacy. Citizens in countries with repressive governments have long used Tor to circumvent firewalls and evade government surveillance.

“As a precaution, we are alerting you that your Twitter account is one of a small group of accounts that may have been targeted by state-sponsored actors,” the emails from Twitter said.

Pursuing a Revamped Image

The Saudis’ sometimes ruthless image-making campaign is also a byproduct of the kingdom’s increasingly fragile position internationally. For decades, their coffers bursting from the world’s thirst for oil, Saudi leaders cared little about what other countries thought of the kingdom, its governance or its anachronistic restrictions on women.

But Saudi Arabia is confronting a more uncertain economic future as oil prices have fallen and competition among energy suppliers has grown, and Crown Prince Mohammed has tried relentlessly to attract foreign investment into the country — in part by portraying it as a vibrant, more socially progressive country than it once was.

Yet the government’s social media manipulation tracks with crackdowns in recent years in other authoritarian states, said Alexei Abrahams, a research fellow at Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto.

Even for conversations involving millions of tweets, a few hundred or a few thousand influential accounts drive the discussion, he said, citing new research. The Saudi government appears to have realized this and tried to take control of the conversation, he added.

“From the regime’s point of view,” he said, “if there are only a few thousand accounts driving the discourse, you can just buy or threaten the activists, and that significantly shapes the conversation.”

As the Saudi government tried to remake its image, it carefully tracked how some of its more controversial decisions were received, and how the country’s most influential citizens online shaped those perceptions.

After the country announced economic austerity measures in 2015 to offset low oil prices and control a widening budget gap, McKinsey & Company, the consulting firm, measured the public reception of those policies.

In a nine-page report, a copy of which was obtained by The Times, McKinsey found that the measures received twice as much coverage on Twitter than in the country’s traditional news media or blogs, and that negative sentiment far outweighed positive reactions on social media.

Three people were driving the conversation on Twitter, the firm found: the writer Khalid al-Alkami; Mr. Abdulaziz, the young dissident living in Canada; and an anonymous user who went by Ahmad.

After the report was issued, Mr. Alkami was arrested, the human rights group ALQST said. Mr. Abdulaziz said that Saudi government officials imprisoned two of his brothers and hacked his cellphone, an account supported by a researcher at Citizen Lab. Ahmad, the anonymous account, was shut down.

A version of this article appears in print on

of the New York edition

with the headline:

Saudis Smother Dissent, Unleashing Troll Army And a Twitter Insider

. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

Read More | https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/20/us/politics/saudi-image-campaign-twitter.html |

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider, in 2018-10-20 16:40:06

0 notes

Text

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider http://www.nature-business.com/nature-saudis-image-makers-a-troll-army-and-a-twitter-insider/

Nature

Image

Online attackers who targeted Jamal Khashoggi were part of a broad effort ordered by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his close advisers to silence Saudi critics.CreditCreditChris J. Ratcliffe/Getty Images

Each morning, Jamal Khashoggi would check his phone to discover what fresh hell had been unleashed while he was sleeping.

He would see the work of an army of Twitter trolls, ordered to attack him and other influential Saudis who had criticized the kingdom’s leaders. He sometimes took the attacks personally, so friends made a point of calling frequently to check on his mental state.

“The mornings were the worst for him because he would wake up to the equivalent of sustained gunfire online,” said Maggie Mitchell Salem, a friend of Mr. Khashoggi’s for more than 15 years.

Mr. Khashoggi’s online attackers were part of a broad effort dictated by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his close advisers to silence critics both inside Saudi Arabia and abroad. Hundreds of people work at a so-called troll farm in Riyadh to smother the voices of dissidents like Mr. Khashoggi. The vigorous push also appears to include the grooming — not previously reported — of a Saudi employee at Twitter whom Western intelligence officials suspected of spying on user accounts to help the Saudi leadership.

The killing by Saudi agents of Mr. Khashoggi, a columnist for The Washington Post, has focused the world’s attention on the kingdom’s intimidation campaign against influential voices raising questions about the darker side of the crown prince. The young royal has tightened his grip on the kingdom while presenting himself in Western capitals as the man to reform the hidebound Saudi state.

This portrait of the kingdom’s image management crusade is based on interviews with seven people involved in those efforts or briefed on them; activists and experts who have studied them; and American and Saudi officials, along with messages seen by The New York Times that described the inner workings of the troll farm.

Saudi operatives have mobilized to harass critics on Twitter, a wildly popular platform for news in the kingdom since the Arab Spring uprisings began in 2010. Saud al-Qahtani, a top adviser to Crown Prince Mohammed who was fired on Saturday in the fallout from Mr. Khashoggi’s killing, was the strategist behind the operation, according to United States and Saudi officials, as well as activist organizations.

Many Saudis had hoped that Twitter would democratize discourse by giving everyday citizens a voice, but Saudi Arabia has instead become an illustration of how authoritarian governments can manipulate social media to silence or drown out critical voices while spreading its own version of reality.

“In the Gulf, the stakes are so high for those who engage in dissent that the benefits of using social media are outweighed by the negatives, and in Saudi Arabia in particular,” said Marc Owen Jones, a lecturer in the history of the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula at Exeter University in Britain.

Neither Saudi officials nor Mr. Qahtani responded to requests for comment about the kingdom’s efforts to control online conversations.

Before his death, Mr. Khashoggi was launching projects to combat online abuse and to try to reveal that Crown Prince Mohammed was mismanaging the country. In September, Mr. Khashoggi wired $5,000 to Omar Abdulaziz, a Saudi dissident living in Canada, who was creating a volunteer army to combat the government trolls on Twitter. The volunteers called themselves the “Electronic Bees.”

Eleven days before Mr. Khashoggi died in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, he wrote on Twitter that the Bees were coming.

Swarming and Stifling Critics on Twitter

One arm of the crackdown on dissidents originates from offices and homes in and around Riyadh, where hundreds of young men hunt on Twitter for voices and conversations to silence. This is the troll farm, described by three people briefed on the project and the messages among group members.

Image

The Saudi government has hired hundreds of men to harass detractors on Twitter, which has had trouble combating their attacks.CreditDavid Paul Morris/Bloomberg

Its directors routinely discuss ways to combat dissent, settling on sensitive themes like the war in Yemen or women’s rights. They then turn to their well-organized army of “social media specialists” via group chats in apps like WhatsApp and Telegram, sending them lists of people to threaten, insult and intimidate; daily tweet quotas to fill; and pro-government messages to augment.

The bosses also send memes that their employees can use to mock dissenters, like an image of Crown Prince Mohammed dancing with a sword, akin to the cartoons of Pepe the Frog that supporters of President Trump used to undermine opponents.

The specialists scour Twitter for conversations on the assigned topics and post messages from the several accounts they each run. Sometimes, when contentious discussions take off, they publish pornographic images to goose engagement with their own posts and distract users from more relevant conversations.

Other times, if one account is blocked by too many other users, they simply close it and open a new one.

In one conversation viewed by The Times, dozens of leaders decided to mute critics of Saudi Arabia’s military attacks on Yemen by reporting the messages to Twitter as “sensitive.” Twitter automatically hides such reported posts from other users, blunting their impact.

Twitter has had difficulty combating the trolls. The company can detect and disable the machine-like behaviors of bot accounts, but it has a harder time picking up on the humans tweeting on behalf of the Saudi government.

The specialists found the jobs through Twitter itself, responding to ads that said only that an employer sought young men willing to tweet for about 10,000 Saudi riyals a month, equivalent to about $3,000.

The political nature of the work was revealed only after they were interviewed and expressed interest in the job. According to the people The Times interviewed, some of the specialists felt they would have been targeted as possible dissenters themselves if they had turned down the job.

The specialists heard directors speak often of Mr. Qahtani. Labeled by activists and writers as the “troll master,” “Saudi Arabia’s Steve Bannon” and “lord of the flies” — for the bots and online attackers sometimes called “flies” by their victims — Mr. Qahtani had gained influence since the young crown prince consolidated power.

He ran media operations inside the royal court, which involved directing the country’s local media, arranging interviews for foreign journalists with the crown prince, and using his Twitter following of 1.35 million to marshal the kingdom’s online defenders against enemies including Qatar, Iran and Canada, as well as dissident Saudi voices like Mr. Khashoggi’s.

For a while, he tweeted using the hashtag #The_Black_List, calling on his followers to suggest perceived enemies of the kingdom.

“Saudi Arabia and its brothers do what they say. That’s a promise,” he tweeted last year. “Add every name you think should be added to #The_Black_List using the hashtag. We will filter them and track them starting now.”

A Suspected Mole Inside Twitter

Twitter executives first became aware of a possible plot to infiltrate user accounts at the end of 2015, when Western intelligence officials told them that the Saudis were grooming an employee, Ali Alzabarah, to spy on the accounts of dissidents and others, according to five people briefed on the matter. They requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

Mr. Alzabarah had joined Twitter in 2013 and had risen through the ranks to an engineering position that gave him access to the personal information and account activity of Twitter’s users, including phone numbers and I.P. addresses, unique identifiers for devices connected to the internet.

The intelligence officials told the Twitter executives that Mr. Alzabarah had grown closer to Saudi intelligence operatives, who eventually persuaded him to peer into several user accounts, according to three of the people briefed on the matter.

Image

Before his killing, Mr. Khashoggi was starting projects to combat online abuse.CreditShannon Stapleton/Reuters

Caught off guard by the government outreach, the Twitter executives placed Mr. Alzabarah on administrative leave, questioned him and conducted a forensic analysis to determine what information he may have accessed. They could not find evidence that he had handed over Twitter data to the Saudi government, but they nonetheless fired him in December 2015.

Mr. Alzabarah returned to Saudi Arabia shortly after, taking few possessions with him. He now works with the Saudi government, a person briefed on the matter said.

A spokesman for Twitter declined to comment. Mr. Alzabarah did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Saudi officials.

On Dec. 11, 2015, Twitter sent out safety notices to the owners of a few dozen accounts Mr. Alzabarah had accessed. Among them were security and privacy researchers, surveillance specialists, policy academics and journalists. A number of them worked for the Tor project, an organization that trains activists and reporters on how to protect their privacy. Citizens in countries with repressive governments have long used Tor to circumvent firewalls and evade government surveillance.

“As a precaution, we are alerting you that your Twitter account is one of a small group of accounts that may have been targeted by state-sponsored actors,” the emails from Twitter said.

Pursuing a Revamped Image

The Saudis’ sometimes ruthless image-making campaign is also a byproduct of the kingdom’s increasingly fragile position internationally. For decades, their coffers bursting from the world’s thirst for oil, Saudi leaders cared little about what other countries thought of the kingdom, its governance or its anachronistic restrictions on women.

But Saudi Arabia is confronting a more uncertain economic future as oil prices have fallen and competition among energy suppliers has grown, and Crown Prince Mohammed has tried relentlessly to attract foreign investment into the country — in part by portraying it as a vibrant, more socially progressive country than it once was.

Yet the government’s social media manipulation tracks with crackdowns in recent years in other authoritarian states, said Alexei Abrahams, a research fellow at Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto.

Even for conversations involving millions of tweets, a few hundred or a few thousand influential accounts drive the discussion, he said, citing new research. The Saudi government appears to have realized this and tried to take control of the conversation, he added.

“From the regime’s point of view,” he said, “if there are only a few thousand accounts driving the discourse, you can just buy or threaten the activists, and that significantly shapes the conversation.”

As the Saudi government tried to remake its image, it carefully tracked how some of its more controversial decisions were received, and how the country’s most influential citizens online shaped those perceptions.

After the country announced economic austerity measures in 2015 to offset low oil prices and control a widening budget gap, McKinsey & Company, the consulting firm, measured the public reception of those policies.

In a nine-page report, a copy of which was obtained by The Times, McKinsey found that the measures received twice as much coverage on Twitter than in the country’s traditional news media or blogs, and that negative sentiment far outweighed positive reactions on social media.

Three people were driving the conversation on Twitter, the firm found: the writer Khalid al-Alkami; Mr. Abdulaziz, the young dissident living in Canada; and an anonymous user who went by Ahmad.

After the report was issued, Mr. Alkami was arrested, the human rights group ALQST said. Mr. Abdulaziz said that Saudi government officials imprisoned two of his brothers and hacked his cellphone, an account supported by a researcher at Citizen Lab. Ahmad, the anonymous account, was shut down.

A version of this article appears in print on

of the New York edition

with the headline:

Saudis Smother Dissent, Unleashing Troll Army And a Twitter Insider

. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

Read More | https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/20/us/politics/saudi-image-campaign-twitter.html |

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider, in 2018-10-20 16:40:06

0 notes

Text

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider https://ift.tt/2yTN06n

Nature

Image

Online attackers who targeted Jamal Khashoggi were part of a broad effort ordered by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his close advisers to silence Saudi critics.CreditCreditChris J. Ratcliffe/Getty Images

Each morning, Jamal Khashoggi would check his phone to discover what fresh hell had been unleashed while he was sleeping.

He would see the work of an army of Twitter trolls, ordered to attack him and other influential Saudis who had criticized the kingdom’s leaders. He sometimes took the attacks personally, so friends made a point of calling frequently to check on his mental state.

“The mornings were the worst for him because he would wake up to the equivalent of sustained gunfire online,” said Maggie Mitchell Salem, a friend of Mr. Khashoggi’s for more than 15 years.

Mr. Khashoggi’s online attackers were part of a broad effort dictated by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his close advisers to silence critics both inside Saudi Arabia and abroad. Hundreds of people work at a so-called troll farm in Riyadh to smother the voices of dissidents like Mr. Khashoggi. The vigorous push also appears to include the grooming — not previously reported — of a Saudi employee at Twitter whom Western intelligence officials suspected of spying on user accounts to help the Saudi leadership.

The killing by Saudi agents of Mr. Khashoggi, a columnist for The Washington Post, has focused the world’s attention on the kingdom’s intimidation campaign against influential voices raising questions about the darker side of the crown prince. The young royal has tightened his grip on the kingdom while presenting himself in Western capitals as the man to reform the hidebound Saudi state.

This portrait of the kingdom’s image management crusade is based on interviews with seven people involved in those efforts or briefed on them; activists and experts who have studied them; and American and Saudi officials, along with messages seen by The New York Times that described the inner workings of the troll farm.

Saudi operatives have mobilized to harass critics on Twitter, a wildly popular platform for news in the kingdom since the Arab Spring uprisings began in 2010. Saud al-Qahtani, a top adviser to Crown Prince Mohammed who was fired on Saturday in the fallout from Mr. Khashoggi’s killing, was the strategist behind the operation, according to United States and Saudi officials, as well as activist organizations.

Many Saudis had hoped that Twitter would democratize discourse by giving everyday citizens a voice, but Saudi Arabia has instead become an illustration of how authoritarian governments can manipulate social media to silence or drown out critical voices while spreading its own version of reality.

“In the Gulf, the stakes are so high for those who engage in dissent that the benefits of using social media are outweighed by the negatives, and in Saudi Arabia in particular,” said Marc Owen Jones, a lecturer in the history of the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula at Exeter University in Britain.

Neither Saudi officials nor Mr. Qahtani responded to requests for comment about the kingdom’s efforts to control online conversations.

Before his death, Mr. Khashoggi was launching projects to combat online abuse and to try to reveal that Crown Prince Mohammed was mismanaging the country. In September, Mr. Khashoggi wired $5,000 to Omar Abdulaziz, a Saudi dissident living in Canada, who was creating a volunteer army to combat the government trolls on Twitter. The volunteers called themselves the “Electronic Bees.”

Eleven days before Mr. Khashoggi died in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, he wrote on Twitter that the Bees were coming.

Swarming and Stifling Critics on Twitter

One arm of the crackdown on dissidents originates from offices and homes in and around Riyadh, where hundreds of young men hunt on Twitter for voices and conversations to silence. This is the troll farm, described by three people briefed on the project and the messages among group members.

Image

The Saudi government has hired hundreds of men to harass detractors on Twitter, which has had trouble combating their attacks.CreditDavid Paul Morris/Bloomberg

Its directors routinely discuss ways to combat dissent, settling on sensitive themes like the war in Yemen or women’s rights. They then turn to their well-organized army of “social media specialists” via group chats in apps like WhatsApp and Telegram, sending them lists of people to threaten, insult and intimidate; daily tweet quotas to fill; and pro-government messages to augment.

The bosses also send memes that their employees can use to mock dissenters, like an image of Crown Prince Mohammed dancing with a sword, akin to the cartoons of Pepe the Frog that supporters of President Trump used to undermine opponents.

The specialists scour Twitter for conversations on the assigned topics and post messages from the several accounts they each run. Sometimes, when contentious discussions take off, they publish pornographic images to goose engagement with their own posts and distract users from more relevant conversations.

Other times, if one account is blocked by too many other users, they simply close it and open a new one.

In one conversation viewed by The Times, dozens of leaders decided to mute critics of Saudi Arabia’s military attacks on Yemen by reporting the messages to Twitter as “sensitive.” Twitter automatically hides such reported posts from other users, blunting their impact.

Twitter has had difficulty combating the trolls. The company can detect and disable the machine-like behaviors of bot accounts, but it has a harder time picking up on the humans tweeting on behalf of the Saudi government.

The specialists found the jobs through Twitter itself, responding to ads that said only that an employer sought young men willing to tweet for about 10,000 Saudi riyals a month, equivalent to about $3,000.

The political nature of the work was revealed only after they were interviewed and expressed interest in the job. According to the people The Times interviewed, some of the specialists felt they would have been targeted as possible dissenters themselves if they had turned down the job.

The specialists heard directors speak often of Mr. Qahtani. Labeled by activists and writers as the “troll master,” “Saudi Arabia’s Steve Bannon” and “lord of the flies” — for the bots and online attackers sometimes called “flies” by their victims — Mr. Qahtani had gained influence since the young crown prince consolidated power.

He ran media operations inside the royal court, which involved directing the country’s local media, arranging interviews for foreign journalists with the crown prince, and using his Twitter following of 1.35 million to marshal the kingdom’s online defenders against enemies including Qatar, Iran and Canada, as well as dissident Saudi voices like Mr. Khashoggi’s.

For a while, he tweeted using the hashtag #The_Black_List, calling on his followers to suggest perceived enemies of the kingdom.

“Saudi Arabia and its brothers do what they say. That’s a promise,” he tweeted last year. “Add every name you think should be added to #The_Black_List using the hashtag. We will filter them and track them starting now.”

A Suspected Mole Inside Twitter

Twitter executives first became aware of a possible plot to infiltrate user accounts at the end of 2015, when Western intelligence officials told them that the Saudis were grooming an employee, Ali Alzabarah, to spy on the accounts of dissidents and others, according to five people briefed on the matter. They requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

Mr. Alzabarah had joined Twitter in 2013 and had risen through the ranks to an engineering position that gave him access to the personal information and account activity of Twitter’s users, including phone numbers and I.P. addresses, unique identifiers for devices connected to the internet.

The intelligence officials told the Twitter executives that Mr. Alzabarah had grown closer to Saudi intelligence operatives, who eventually persuaded him to peer into several user accounts, according to three of the people briefed on the matter.

Image

Before his killing, Mr. Khashoggi was starting projects to combat online abuse.CreditShannon Stapleton/Reuters

Caught off guard by the government outreach, the Twitter executives placed Mr. Alzabarah on administrative leave, questioned him and conducted a forensic analysis to determine what information he may have accessed. They could not find evidence that he had handed over Twitter data to the Saudi government, but they nonetheless fired him in December 2015.

Mr. Alzabarah returned to Saudi Arabia shortly after, taking few possessions with him. He now works with the Saudi government, a person briefed on the matter said.

A spokesman for Twitter declined to comment. Mr. Alzabarah did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Saudi officials.

On Dec. 11, 2015, Twitter sent out safety notices to the owners of a few dozen accounts Mr. Alzabarah had accessed. Among them were security and privacy researchers, surveillance specialists, policy academics and journalists. A number of them worked for the Tor project, an organization that trains activists and reporters on how to protect their privacy. Citizens in countries with repressive governments have long used Tor to circumvent firewalls and evade government surveillance.

“As a precaution, we are alerting you that your Twitter account is one of a small group of accounts that may have been targeted by state-sponsored actors,” the emails from Twitter said.

Pursuing a Revamped Image

The Saudis’ sometimes ruthless image-making campaign is also a byproduct of the kingdom’s increasingly fragile position internationally. For decades, their coffers bursting from the world’s thirst for oil, Saudi leaders cared little about what other countries thought of the kingdom, its governance or its anachronistic restrictions on women.

But Saudi Arabia is confronting a more uncertain economic future as oil prices have fallen and competition among energy suppliers has grown, and Crown Prince Mohammed has tried relentlessly to attract foreign investment into the country — in part by portraying it as a vibrant, more socially progressive country than it once was.

Yet the government’s social media manipulation tracks with crackdowns in recent years in other authoritarian states, said Alexei Abrahams, a research fellow at Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto.

Even for conversations involving millions of tweets, a few hundred or a few thousand influential accounts drive the discussion, he said, citing new research. The Saudi government appears to have realized this and tried to take control of the conversation, he added.

“From the regime’s point of view,” he said, “if there are only a few thousand accounts driving the discourse, you can just buy or threaten the activists, and that significantly shapes the conversation.”

As the Saudi government tried to remake its image, it carefully tracked how some of its more controversial decisions were received, and how the country’s most influential citizens online shaped those perceptions.

After the country announced economic austerity measures in 2015 to offset low oil prices and control a widening budget gap, McKinsey & Company, the consulting firm, measured the public reception of those policies.

In a nine-page report, a copy of which was obtained by The Times, McKinsey found that the measures received twice as much coverage on Twitter than in the country’s traditional news media or blogs, and that negative sentiment far outweighed positive reactions on social media.

Three people were driving the conversation on Twitter, the firm found: the writer Khalid al-Alkami; Mr. Abdulaziz, the young dissident living in Canada; and an anonymous user who went by Ahmad.

After the report was issued, Mr. Alkami was arrested, the human rights group ALQST said. Mr. Abdulaziz said that Saudi government officials imprisoned two of his brothers and hacked his cellphone, an account supported by a researcher at Citizen Lab. Ahmad, the anonymous account, was shut down.

A version of this article appears in print on

of the New York edition

with the headline:

Saudis Smother Dissent, Unleashing Troll Army And a Twitter Insider

. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

Read More | https://ift.tt/2EAIcZN |

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider, in 2018-10-20 16:40:06

0 notes

Text

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider

Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider Nature Saudis’ Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider http://www.nature-business.com/nature-saudis-image-makers-a-troll-army-and-a-twitter-insider/

Nature

Image

Online attackers who targeted Jamal Khashoggi were part of a broad effort ordered by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his close advisers to silence Saudi critics.CreditCreditChris J. Ratcliffe/Getty Images

Each morning, Jamal Khashoggi would check his phone to discover what fresh hell had been unleashed while he was sleeping.

He would see the work of an army of Twitter trolls, ordered to attack him and other influential Saudis who had criticized the kingdom’s leaders. He sometimes took the attacks personally, so friends made a point of calling frequently to check on his mental state.

“The mornings were the worst for him because he would wake up to the equivalent of sustained gunfire online,” said Maggie Mitchell Salem, a friend of Mr. Khashoggi’s for more than 15 years.

Mr. Khashoggi’s online attackers were part of a broad effort dictated by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his close advisers to silence critics both inside Saudi Arabia and abroad. Hundreds of people work at a so-called troll farm in Riyadh to smother the voices of dissidents like Mr. Khashoggi. The vigorous push also appears to include the grooming — not previously reported — of a Saudi employee at Twitter whom Western intelligence officials suspected of spying on user accounts to help the Saudi leadership.

The killing by Saudi agents of Mr. Khashoggi, a columnist for The Washington Post, has focused the world’s attention on the kingdom’s intimidation campaign against influential voices raising questions about the darker side of the crown prince. The young royal has tightened his grip on the kingdom while presenting himself in Western capitals as the man to reform the hidebound Saudi state.

This portrait of the kingdom’s image management crusade is based on interviews with seven people involved in those efforts or briefed on them; activists and experts who have studied them; and American and Saudi officials, along with messages seen by The New York Times that described the inner workings of the troll farm.

Saudi operatives have mobilized to harass critics on Twitter, a wildly popular platform for news in the kingdom since the Arab Spring uprisings began in 2010. Saud al-Qahtani, a top adviser to Crown Prince Mohammed who was fired on Saturday in the fallout from Mr. Khashoggi’s killing, was the strategist behind the operation, according to United States and Saudi officials, as well as activist organizations.

Many Saudis had hoped that Twitter would democratize discourse by giving everyday citizens a voice, but Saudi Arabia has instead become an illustration of how authoritarian governments can manipulate social media to silence or drown out critical voices while spreading its own version of reality.

“In the Gulf, the stakes are so high for those who engage in dissent that the benefits of using social media are outweighed by the negatives, and in Saudi Arabia in particular,” said Marc Owen Jones, a lecturer in the history of the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula at Exeter University in Britain.

Neither Saudi officials nor Mr. Qahtani responded to requests for comment about the kingdom’s efforts to control online conversations.

Before his death, Mr. Khashoggi was launching projects to combat online abuse and to try to reveal that Crown Prince Mohammed was mismanaging the country. In September, Mr. Khashoggi wired $5,000 to Omar Abdulaziz, a Saudi dissident living in Canada, who was creating a volunteer army to combat the government trolls on Twitter. The volunteers called themselves the “Electronic Bees.”

Eleven days before Mr. Khashoggi died in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, he wrote on Twitter that the Bees were coming.

Swarming and Stifling Critics on Twitter

One arm of the crackdown on dissidents originates from offices and homes in and around Riyadh, where hundreds of young men hunt on Twitter for voices and conversations to silence. This is the troll farm, described by three people briefed on the project and the messages among group members.

Image

The Saudi government has hired hundreds of men to harass detractors on Twitter, which has had trouble combating their attacks.CreditDavid Paul Morris/Bloomberg

Its directors routinely discuss ways to combat dissent, settling on sensitive themes like the war in Yemen or women’s rights. They then turn to their well-organized army of “social media specialists” via group chats in apps like WhatsApp and Telegram, sending them lists of people to threaten, insult and intimidate; daily tweet quotas to fill; and pro-government messages to augment.

The bosses also send memes that their employees can use to mock dissenters, like an image of Crown Prince Mohammed dancing with a sword, akin to the cartoons of Pepe the Frog that supporters of President Trump used to undermine opponents.

The specialists scour Twitter for conversations on the assigned topics and post messages from the several accounts they each run. Sometimes, when contentious discussions take off, they publish pornographic images to goose engagement with their own posts and distract users from more relevant conversations.

Other times, if one account is blocked by too many other users, they simply close it and open a new one.

In one conversation viewed by The Times, dozens of leaders decided to mute critics of Saudi Arabia’s military attacks on Yemen by reporting the messages to Twitter as “sensitive.” Twitter automatically hides such reported posts from other users, blunting their impact.

Twitter has had difficulty combating the trolls. The company can detect and disable the machine-like behaviors of bot accounts, but it has a harder time picking up on the humans tweeting on behalf of the Saudi government.

The specialists found the jobs through Twitter itself, responding to ads that said only that an employer sought young men willing to tweet for about 10,000 Saudi riyals a month, equivalent to about $3,000.

The political nature of the work was revealed only after they were interviewed and expressed interest in the job. According to the people The Times interviewed, some of the specialists felt they would have been targeted as possible dissenters themselves if they had turned down the job.

The specialists heard directors speak often of Mr. Qahtani. Labeled by activists and writers as the “troll master,” “Saudi Arabia’s Steve Bannon” and “lord of the flies” — for the bots and online attackers sometimes called “flies” by their victims — Mr. Qahtani had gained influence since the young crown prince consolidated power.

He ran media operations inside the royal court, which involved directing the country’s local media, arranging interviews for foreign journalists with the crown prince, and using his Twitter following of 1.35 million to marshal the kingdom’s online defenders against enemies including Qatar, Iran and Canada, as well as dissident Saudi voices like Mr. Khashoggi’s.

For a while, he tweeted using the hashtag #The_Black_List, calling on his followers to suggest perceived enemies of the kingdom.

“Saudi Arabia and its brothers do what they say. That’s a promise,” he tweeted last year. “Add every name you think should be added to #The_Black_List using the hashtag. We will filter them and track them starting now.”

A Suspected Mole Inside Twitter

Twitter executives first became aware of a possible plot to infiltrate user accounts at the end of 2015, when Western intelligence officials told them that the Saudis were grooming an employee, Ali Alzabarah, to spy on the accounts of dissidents and others, according to five people briefed on the matter. They requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

Mr. Alzabarah had joined Twitter in 2013 and had risen through the ranks to an engineering position that gave him access to the personal information and account activity of Twitter’s users, including phone numbers and I.P. addresses, unique identifiers for devices connected to the internet.

The intelligence officials told the Twitter executives that Mr. Alzabarah had grown closer to Saudi intelligence operatives, who eventually persuaded him to peer into several user accounts, according to three of the people briefed on the matter.

Image

Before his killing, Mr. Khashoggi was starting projects to combat online abuse.CreditShannon Stapleton/Reuters

Caught off guard by the government outreach, the Twitter executives placed Mr. Alzabarah on administrative leave, questioned him and conducted a forensic analysis to determine what information he may have accessed. They could not find evidence that he had handed over Twitter data to the Saudi government, but they nonetheless fired him in December 2015.

Mr. Alzabarah returned to Saudi Arabia shortly after, taking few possessions with him. He now works with the Saudi government, a person briefed on the matter said.

A spokesman for Twitter declined to comment. Mr. Alzabarah did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Saudi officials.

On Dec. 11, 2015, Twitter sent out safety notices to the owners of a few dozen accounts Mr. Alzabarah had accessed. Among them were security and privacy researchers, surveillance specialists, policy academics and journalists. A number of them worked for the Tor project, an organization that trains activists and reporters on how to protect their privacy. Citizens in countries with repressive governments have long used Tor to circumvent firewalls and evade government surveillance.

“As a precaution, we are alerting you that your Twitter account is one of a small group of accounts that may have been targeted by state-sponsored actors,” the emails from Twitter said.

Pursuing a Revamped Image

The Saudis’ sometimes ruthless image-making campaign is also a byproduct of the kingdom’s increasingly fragile position internationally. For decades, their coffers bursting from the world’s thirst for oil, Saudi leaders cared little about what other countries thought of the kingdom, its governance or its anachronistic restrictions on women.

But Saudi Arabia is confronting a more uncertain economic future as oil prices have fallen and competition among energy suppliers has grown, and Crown Prince Mohammed has tried relentlessly to attract foreign investment into the country — in part by portraying it as a vibrant, more socially progressive country than it once was.

Yet the government’s social media manipulation tracks with crackdowns in recent years in other authoritarian states, said Alexei Abrahams, a research fellow at Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto.

Even for conversations involving millions of tweets, a few hundred or a few thousand influential accounts drive the discussion, he said, citing new research. The Saudi government appears to have realized this and tried to take control of the conversation, he added.